Sharing data in EHR systems without consumer preferences may lead to information withholding

An unintended, if not wholly unexpected, consequence of the health care industry’s heavily incentivized move towards use of electronic health records and sharing data contained in those records appears to be a greater likelihood that individuals will withhold information from their doctors or other medical providers to prevent the possibility of the information being shared with others. According to the results of a study released on Monday by the California HealthCare Foundation on consumers and health information technology, about one in six respondents said they would conceal information from their doctors if their medical data was to be stored in an EHR system that enabled health data sharing with entities beyond the provider, and another third would consider concealing information. The study also found that when individuals begin using personal health records (PHR), they become more involved in their own health care and know more about their own health. National adoption rates for PHRs remain quite low overall, but have shown tremendous growth in the past couple of years, a trend which is generally expected to continue in parallel with the anticipated rise in health care industry penetration of EHR systems.

The lingering general concerns over patient privacy are hardly surprising, particularly given the lack of attention given to date on enabling individuals to assert more control over the use and dissemination of their personal health information. Interestingly, the CHCF study found that while PHR users are concerned about the privacy and security of their data stored in PHR systems, they are not so worried about privacy as to believe that privacy issues should stand in the way of evaluating and realizing some of the anticipated benefits of health IT. Privacy advocates continue to stress the importance of adding support for consumer preferences and, especially, soliciting and managing consent for disclosure of personal health information either based on the content of the data or the use for which it is being disclosed. Too much discretion with respect to health record disclosure can have the same result as withholding information from doctors: when electronic health records are consulted for use in clinical care settings, the providers doing the treatment may be making decisions based on incomplete medical information. This situation subverts the key health information sharing objectives such as improving the quality of care or reducing negative outcomes due to errors. Health information exchange providers, including government entities, will need to continue to balance health care and public health outcomes with individual expectations of privacy and support for privacy principles such as individual choice and disclosure limitations.

Key government security initiatives making slower than anticipated progress

The Government Accountability Office released two reports, completed in March and released publicly on Monday, that highlight slower-than-expected progress being made on key government-wide information security initiatives. The first report focuses on the Federal Desktop Core Configuration (FDCC) program, which mandates minimum security baselines for client computers in federal agencies running Windows operating systems (so far it covers XP and Vista). The program is managed by the National Institute of Standards and Technology, who publishes the secure configuration specifications (akin to DISA security technical implementation guides but somewhat less robust and covering fewer types of systems) and produced the XML-based security content automation protocol (SCAP) to facilitate the process of validating secure configuration settings using automated scanning tools. FDCC compliance has been required for federal agencies since February 1, 2008, with agencies obligated to test and validate appropriate security settings for computers in their environments as part of the continuous monitoring required under FISMA. The GAO report notes that as of last September, none of the 24 major executive agencies had adopted the required FDCC settings on all applicable workstations, and 6 of the 24 had yet to acquire a tool capable of monitoring configurations using SCAP. In the aggregate, it appears that agencies do not consider deviations from FDCC configuration settings to be a source of significant security risk, as many agencies that reported such deviations also indicated they had no plans to mitigate them. For its part, GAO’s recommendations for FDCC seem largely focused on improving agency education and support for implement FDCC monitoring and achieving compliance. The report also included agency-specific recommendations for 22 of 24 agencies.

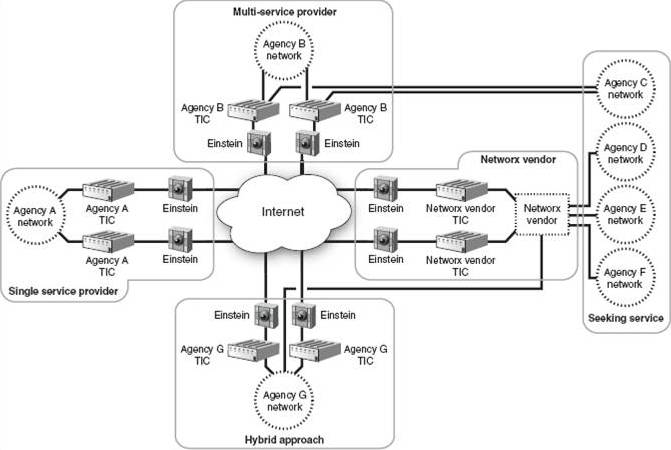

The second report addresses progress to date on the government’s initiative to secure agency connections to the Internet under the Trusted Internet Connections (TIC) program, which was announced in late 2007. Under TIC, agencies were instructed to drastically reduce the number of connections of their networks to the Internet, with an overall program goal of reducing total government Internet connections to 100 or fewer. Agencies were required, as part of their IT infrastructure planning, to propose a target number of Internet connections (and the locations of those connections) to OMB by the end of June 2008. As an interim milestone, under TIC agencies were supposed to reduce the total number of existing Internet connections to approximately 1,500 by then end of the 2009 fiscal year, but GAO found that overall the government was running about 15% short of that goal, and of the 19 agencies reporting the status of their connection consolidation efforts, none had reached an 80-100% level of progress, and just about every agency still has far more Internet connections than they “should” based on the plans of action they produced more than 18 months ago. While it’s possible that the overall targets and timeline for the TIC initiative were overly ambitious or unrealistic, there remains a sense of urgency regarding TIC because of its relation to one of the key national critical infrastructure protection programs, the Department of Homeland Security’s Einstein intrusion monitoring system, which itself is in pilot phase with aggressive plans for widescale roll-out. The Einstein program predates the TIC by several years, but the practical implementation of comprehensive government network traffic monitoring is something only made feasible if the number of sites being monitored is reduced to a manageable number.

The vision for Einstein (as shown in the graphic above, which appears in the GAO report) includes placing intrusion detection sensors at every TIC-approved point of connection to the Internet, although in practice the number of monitoring sites may be less than suggested by TIC connection counts if DHS succeeds in deploying the Einstein system within the environments of major network service providers to the government.

Mistakes in UK NHS organ donor consent data show importance of validating data from outside sources

As reported in the Daily Telegraph, the British National Health Service (NHS) is blaming an IT error for the presence of inaccurate consent information for about 800,000 people about their wishes for organ donation after death. As a result of the incorrect consent information, organs were harvested from as many as 20 people whose consent had not in fact been given prior to their death. The information about organ donation preferences was initially captured — as it often is in the U.S. — as part of the process of obtaining a driver’s license. Data from the Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency was transferred to NHS Blood and Transport over 10 years ago. The errors were apparently introduced at the initial time of data transfer, but they weren’t discovered until NHS contacted people it thought had consented to organ donation, as part of a routine written communication program with people in the NHS donor registry.

This incident shows the importance of verifying the accuracy and integrity of data integrated with or retrieved or transferred from external sources, especially given the need to instill trust among individuals whose data will potentially be made available or used by government and private sector organizations under widespread use of electronic health records. This sort of potential for error arises is many data aggregation contexts, notably including U.S. credit reporting bureaus, but when medical conditions or patient preferences are involved, the potential consequences from acting on incorrect information are obviously more serious than a denial of credit.

Because this situation revolves around a very specific form of consent, there are clear parallels to problem of capturing, managing, and honoring consent in electronic health records and health information sharing for a variety of purposes (especially those for which consent is required under the law). Finding ways to manage consumer preferences in health care is an area the U.S. government has been working on since the early days of the American Health Information Community (AHIC), and ONC has been working on consumer preferences since at least 2008, when they were identified as a gap in use cases prioritized for development by the American Health Information Community (AHIC), and the Office of the National Coordinator (ONC) has produced a Consumer Preferences Draft Requirements Document that is likely to serve as a key input should ONC move to add consumer preferences criteria to any of its adopted standards, potentially including adding them to meaningful use criteria.

The desire to be able to rely on data integrated through initiatives such as health information exchange (or, for that matter, the Information Sharing Environment (ISE) in a homeland security context), and the lack of ability to do so, remains a central issue for future intended uses of health IT for clinical decision support. The current state of the industry and the technology is that there is no consistent mechanism for asserting integrity (to be fair, this problem exists for non-electronic records too), and is only one of several issues that can be encountered with composite or virtual data sets. These other data challenges include incompleteness of data, errors due to omission (including those resulting from withholding consent to disclose), Byzantine failure, and the need to reconcile multiple or conflicting values for the same data element as represented in different sources about the same individual.

Virginia enacts limited-scope medical information breach notification law

Last month, the Virginia General Assembly passed a new law, to take effect on January 1, 2011, that will implement new disclosure notification rules for breaches of medical information about Virginia residents. The new law appears intended to fill a fairly narrow perceived gap in information breach disclosure requirements already in place at both the state and federal level, including coverage for medical information specifically as well as personal information generally. The specific attention to medical information makes the new law complementary to several measures passed during the 2008 legislative session that strengthened existing statutes covering crimes involving fraud to add protection against identity theft (§18.2-186.3) and require notification for breaches of personal information (§18.2-186-6). Many of the definitions and notification procedures included in the recently passed bill are the same as those found in the earlier code on breach of personal information notification, including the definitions for a “breach of the security of the system,” what constitutes “notice,” and the applicability of the notification rules even when breached information is encrypted, if the disclosure involves anyone who might have access to the encryption key.

One area where the medical information breach notification definitions differ from current statutory language is in what is considered an “entity” subject to the requirements in question. The rules for breach of personal information notification define an entity quite broadly as “corporations, business trusts, estates, partnerships, limited partnerships, limited liability partnerships, limited liability companies, associations, organizations, joint ventures, governments, governmental subdivisions, agencies, or instrumentalities or any other legal entity, whether for profit or not for profit.” (§18.2-186-6, section A) In contrast, the breach of medical information notification says an entity is “any authority, board, bureau, commission, district or agency of the Commonwealth or of any political subdivision of the Commonwealth, including cities, towns and counties, municipal councils, governing bodies of counties, school boards and planning commissions; boards of visitors of public institutions of higher education; and other organizations, corporations, or agencies in the Commonwealth supported wholly or principally by public funds.” (§32.1-127.1:05, emphasis added) This appears to limit the coverage of the new law to public sector organizations, and to private organizations receiving significant public funding. It is not at all clear that a private sector company operating independently of Virginia funding would be subject to the new rules.

In terms of applicability in the health space, the Virginia law makes no attempt to preempt or augment federal health information breach disclosure requirements under HIPAA or HITECH. Instead, it specifically excludes from coverage any HIPAA-covered entities (defined under the law as health care plans, health care providers, or health care clearinghouses) or business associates of those entities (individuals or organizations that perform functions involving the use or disclosure of protected health information on behalf of a covered entity), and also excepts non-HIPAA covered entities that are subject to the FTC’s health data breach notification rules established under authority of the HITECH Act. Since we’re talking about health data, presumably a large proportion of the wholly private organizations that seem to operate outside the coverage of the new Virginia law would already be subject to federal heath data breach notification laws, but there appears to be a gap in coverage for third-party data stewards, handlers, or transmitters that do not process or transform the data, and therefore do not fall under the definition of health care clearinghouses.As state, regional, and national efforts to facilitate health information exchange continue to develop — whether to satisfy information sharing requirements under meaningful use or to facilitate local or wider scale interoperability among data sources — the Virginia General Assembly might want to consider how medical information breach notification rules can be extended to cover potential new market entrants in health information exchange.

Public-private sector debate on health IT turns to whose security is weakest

Security concerns remain a major sticking point on electronic health records, health IT in general, and greater levels of health information exchange and interoperability among potential public and private sector participants in those exchanges. An article in the Wall Street Journal two weeks ago by Deborah Peel, privacy advocate and founder of the non-profit Patient Privacy Rights, argued that due to the lack of comprehensive privacy, individual consent, and information disclosure controls, medical records simply aren’t secure. The opinion piece, which restates key themes that Peel has been expressing publicly for at least five years, served as fodder for a Fox News commentary that suggested Americans will be reluctant to put their medical data online not just due to the lack of consent and personal control over its disclosure, but because the government will have access to electronic health records. It’s not entirely clear that this is a fair characterization of Peel and other privacy advocates’ position, and it’s certainly a more partisan take that what many insist is an issue that persists regardless of which party is in power.

The tone of the current debate raises another point of contention about whose security is really the most problematic when it comes to protecting health information online. The privacy debate is focused as much on maintaining confidentiality as it is about consent for disclosure or control of data dissemination, so the simple fact that the government’s vision for electronic health records includes widespread interoperability and data exchange among health information systems logically produces an outcome where a given record is potentially accessible to many more parties, be they from government or industry. For all the conservative hand-wringing on this issue, there appear to be just a strong a concern among government agencies about data confidentiality and security measures, but the government’s concerns are about private sector security practices.

Speaking at an AFCEA event on Health IT in Maryland this week, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) CIO Julie Boughn said that the security measures in place among some of the private sector organizations that seek to exchange data with CMS are so lacking in some cases as to be “almost embarrassing.” CMS is in a position to notice such deficiencies going forward as well, as it will serve as the agency administering the measures for meaningful use under which eligible health providers and professionals will seek to qualify for incentive funding to buy, implement, and use electronic health record technology. Boughn has long maintained that, due to the requirements they must follow under FISMA, federal agencies’ information security is stronger than the equivalent security provisions under the HIPAA Security Rule or other security control standards applicable to private sector health care organizations. She echoed that position again this week, suggesting that organizations seeking to use in nationwide health IT infrastructure and participate in health information exchange initiatives with government agencies will have to follow FISMA just as the agencies do.

It’s hard to reconcile the idea of imposing FISMA on non-government agencies with the complete absence of any references to or incorporation of standards or processes from FISMA in either the Health Information Technology for Clinical and Economic Health (HITECH) Act or in the meaningful use measures, EHR certification criteria, and technical standards proposed to date. Instead, the focus for security and privacy in health IT has been strengthening and otherwise revising provisions in the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), the federal regulations codified under which serve as the basis for the single meaningful use measure for security. It seems the government leaders on health IT and the health care industry are pretty closely aligned on using the provisions of both the HIPAA Security and Privacy Rules, so it will be interesting to see if more of the FISMA framework makes its way into the overall health IT picture.

SecurityArchitecture.com

SecurityArchitecture.com