4th Circuit rules that obtaining cell site location data requires a warrant

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit ruled this week in United States v. Graham that requests by law enforcement authorities to obtain and examine historical cell site location data for individual cellular subscribers constitutes a search under the Fourth Amendment and therefore requires a search warrant. In its 2-1 ruling, the Circuit Court explicitly rejected the third-party doctrine approach that both the Fifth and Eleventh Circuits have relied on in contrary rulings finding that reviewing cell site location data – which, the doctrine holds, subscribers voluntarily give to cellular network providers and therefore in which they can have no reasonable expectation of privacy – doesn’t constitute a search. In the specific case the Fourth Circuit heard, the fact that the majority believed the government erred by obtaining a court order under the Stored Communications Act (SCA) instead of a search warrant as required under the Fourth Amendment did not materially impact the outcome for the appellants, as the Circuit Court upheld their convictions and essentially forgave the government because it acted in good faith when it relied on the SCA.

The split among appellate courts on the privacy of cell site location data (among other issues) raises the likelihood that this issue will need to be addressed by the U.S. Supreme Court, just as it has done with global positioning system (GPS) data. In United States v. Graham, the judges seemed to be willing to put cell site location data on the same logical footing as GPS data. Despite the fact that cell site location data is far less precise in determining an individual’s location, the fact that cellular devices are small and usually carried by an individual as they go from public to private locations means, according to this court at least, that cellular device users do have some reasonable expectation of privacy when the cell site location data covers a significant period of time (no court has yet provided a clear standard as to how long is “long enough” to reach the level when a search warrant should be required).

Threat of phishing attacks shows no signs of diminishing

A memo issued by the FBI on July 16 warning federal agencies that government employees are being targeted by a phishing campaign seeking to exploit known vulnerabilities in Adobe Flash is only the most recent indication that phishing has become a favored method of attack against government agencies. As part of their cyber-security awareness efforts, multiple agencies – led by the Department of Homeland Security’s United States Computer Emergency Response Team (US-CERT) – encourage individuals and organizations to report phishing emails, which are a common approach used by hackers to infect government systems with malware or to try to obtain personal or technical information that could be useful in other types of attacks. Network monitoring and intrusion detection and prevention systems employed by the government are often helpful in identifying signs that malware has been introduced into agency environments (such as by noting network traffic flows from government agency sources to foreign or known-to-be-bad destinations) but they don’t appear to be very effective at flagging phishing emails that trick users into clicking on links or opening attachments that cause the infection.

It should come as no surprise that government employees are targeted in phishing scams as much or more often than commercial sector workers, given that many agencies publish employee directories online that include telephone numbers and email addresses. According to research reported by threat intelligence firm Recorded Future, user information including email addresses and login credentials from 47 different U.S. government agencies can be found online. The timeframe during which this information was available spans many months predating the disclosure of the large-scale compromise of government employee and contractor information from the Office of Personnel Management (OPM).

To address to the phishing threat, many agencies are augmenting their security awareness training with exercises, often termed “phishing expeditions,” that entail sending fake phishing emails to employees and contractors and tracking how users respond. These fictional messages are specially designed to look like phishing emails and including tell-tale signs that users have ostensibly been trained to recognize as suspicious. Based on outside observation, the results appear mixed. A small but troubling minority of users (as many as 10 to 15 percent in some agencies) click on links embedded in fake phishing emails and an even smaller number take the preferred action of reporting the suspicious email to an agency’s IT group or incident response team. On a somewhat more positive note, in the wake of the OPM breach, many government employees showed a heightened level of sensitivity towards potential email-based scams when they responded with alarm to email messages they received from the contractor OPM hired to notify individuals affected by the breach, thinking that these legitimate emails were actually phishing attempts. In all likelihood many agencies, particularly in the defense and intelligence arenas, blocked these externally-sourced messages and prevented their employees from receiving them in the first place. It turns out government worker suspicions were well founded: on June 30 US-CERT issued an alert indicating the existence of phishing campaigns related to the OPM breach, presumably capitalizing on the potential confusion regarding notification to affected personnel and identity protection services being made available to them. Because the OPM hack has generally been characterized as intended to harvest personal information for future use – in subsequent spear phishing attacks or to try to coerce individuals to divulge organizational information – the added awareness of phishing attacks in the wake of the OPM incidents may serve to reduce the likelihood that employees and contractors fall for phishing attacks in the future.

WordPress security essentials

Just about eight months ago, SecurityArchitecture.com joined the multitude of websites running WordPress. This change, after more than five years online with a largely custom-coded PHP and HTML setup, enabled a number of stylistic and functional improvements, and facilitated the consolidation of the SecurityArchitecture blog with the rest of the content presented on the site. Adopting a popular platform like WordPress offers a lot of advantages, not least of which is that almost anything you want to do has already been done by someone using WordPress. Similarly, almost any problem or technical issue you might encounter has also been seen (and usually resolved) by someone else. The widespread implementation of WordPress combined with its (relative) ease of use has some negative aspects as well, however, particularly when it comes to cyber security. In much the same way that Microsoft’s Windows operating systems and Windows products face the largest proportion of attacks, malware, and attempted exploits, WordPress is a popular target for attackers, meaning essentially everyone running a WordPress site, no matter how small or off-the-radar, is likely to see a lot of attempted intrusions. While WordPress is famous for its “5-minute install” and an administrative dashboard that requires WordPress users to have little or no technical knowledge to be able to produce a high-quality website, there is almost nothing in the standard installation instructions about security and many WordPress sites are highly vulnerable to attack.

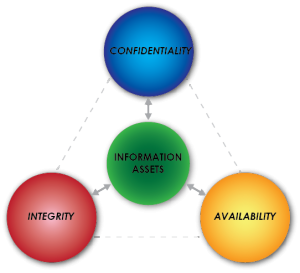

For a site focused on information security, there is an implied obligation to do more (in some cases much more) than the bare minimum when it comes to security. Taking proactive steps to implement a variety of security controls should, however, be a priority for any website. Classic definitions of security include the distinct and inter-related objectives of confidentiality, integrity, and availability, each of which is necessary to maintain the operational state of an application and the data it contains. Conventional information security models also distinguish between preventive, detective, and corrective controls, where we use preventive controls to try to keep unintended or undesirable events from occurring, detective controls to discover when such things have happened, and corrective controls to respond or recover after unwanted events occur. Each of these types of controls is important for a WordPress site, or any application or environment subject to attack. For a web-based application like WordPress, preventive controls typically include firewalls, access controls (like requiring users to log in with a password), and user education like security awareness training. Detective controls include network and application monitoring, vulnerability and malware scanning, and review of audit and event logs. Corrective controls include incident response procedures, file and database backup and recovery capabilities, and (not to be overlooked) planning in advance what to do when something goes wrong.

For a site focused on information security, there is an implied obligation to do more (in some cases much more) than the bare minimum when it comes to security. Taking proactive steps to implement a variety of security controls should, however, be a priority for any website. Classic definitions of security include the distinct and inter-related objectives of confidentiality, integrity, and availability, each of which is necessary to maintain the operational state of an application and the data it contains. Conventional information security models also distinguish between preventive, detective, and corrective controls, where we use preventive controls to try to keep unintended or undesirable events from occurring, detective controls to discover when such things have happened, and corrective controls to respond or recover after unwanted events occur. Each of these types of controls is important for a WordPress site, or any application or environment subject to attack. For a web-based application like WordPress, preventive controls typically include firewalls, access controls (like requiring users to log in with a password), and user education like security awareness training. Detective controls include network and application monitoring, vulnerability and malware scanning, and review of audit and event logs. Corrective controls include incident response procedures, file and database backup and recovery capabilities, and (not to be overlooked) planning in advance what to do when something goes wrong.

The good news for WordPress users is that there are multiple security plugins available that enhance site security, provide routine (even continuous) monitoring, and help administrators remove and repair whatever changes or damage an intrusion has caused. A quick online search for “WordPress security plugins” will return dozens of tools and lots of reviews and opinions about which plugins are the best. It is a pointless exercise to try to arrive at a set of recommendations that will work for every WordPress site, since the features and functional purpose of each site is different. From prior experience across multiple WordPress implementations, however, we believe it is a good idea to select and install security plugins that will 1) strengthen access controls; 2) monitor WordPress for activity or changes that could indicate an attempted or successful intrusion; and 3) help “clean” a compromised site and restore normal function. Most available security plugins overlap to some extent in the features they offer, but to provide a complete set of security controls site administrators often need to deploy more than one tool. Most popular free security plugins provide several of these capabilities that can, if configured and used properly, strengthen protection for WordPress sites.

- Website firewall

- IP address blacklisting

- Brute force prevention

- Login monitoring

- Malware scanning

- File integrity checking

- File permissions

- Database backups

- Activity logging

For commercial, professional, or high-traffic sites, administrators may also want to consider additional subscription services such as active scanning, web application firewalls, denial-of-service protection, and post-intrusion cleanup and restoration services.

No upside to OPM data breaches

In the weeks following the June 4 announcement by the U.S. Office of Personnel Management that it had discovered in April a large-scale security incident that had compromised the personal information of as many as 4 million current and former federal government employees, subsequent disclosures and updates about the incident paint a troubling picture of the poor security practices that facilitated the attack and delayed its discovery. First came the perhaps inevitable revelation that the impact from the incident was worse than initially reported, affecting not only federal employees but millions of former employees and contractors – potentially everyone who applied for a security clearance dating back to 2000, a group that OPM estimates at 21.5 million people.

The initial, smaller group of employees was slated to receive identity theft protection and other measures to help avoid future damage from the loss of their personal information. OPM quickly hired a contractor to assist in the employee notification effort, but in the rush to get the process started OPM apparently failed to consider how affected individuals would perceive email notifications directing them to a non-government site and asking for personal information. Many recipients believed the emails coming from contractor CSID were phishing attempts or raised concerns about providing personal information to the fraud protection companies OPM had engaged. The Army went so far as to warn its employees not to respond to such emails, categorizing them as an attack. OPM subsequently suspended the notifications to defense agencies (although they continued to go to civilian ones). Unfortunately for all concerned, notification emails about the OPM breach and follow-up actions affected individuals can take proved to be irresistible fodder for hackers, as news of phishing attacks surfaced from the U.S. Computer Emergency Response Team (US-CERT).

Aside from the generally unsatisfactory way OPM has handled its response to the data breach (notification to the broader group of security clearance applicants still has yet to begin), information OPM provided to Congress in testimony at a Senate hearing convened by the Appropriations Subcommittee on Financial Services and General Government revealed multiple failures in what should be considered basic information security practices. Perhaps most troubling was the indication by OPM Director Katherine Archuleta that the unauthorized access to OPM’s systems was achieved by compromising user credentials from a contractor, KeyPoint Government Solutions, that was itself the victim of a cyberattack resulting in a data breach of information on thousands of government employees. The implication is that after the intrusion into its contractor’s systems, OPM failed to disable or change credentials it had issued to KeyPoint personnel. Imagine a homeowner who has given a spare house key to his neighbor and, upon learning his neighbor’s house was robbed, chooses not to have his locks changed. The successful use of credentials issued to a contractor is reminiscent of other high-profile data breaches, including the theft of customer information from Home Depot and Target, where hackers first compromised a third party vendor to gain access to the primary target.

Aside from the generally unsatisfactory way OPM has handled its response to the data breach (notification to the broader group of security clearance applicants still has yet to begin), information OPM provided to Congress in testimony at a Senate hearing convened by the Appropriations Subcommittee on Financial Services and General Government revealed multiple failures in what should be considered basic information security practices. Perhaps most troubling was the indication by OPM Director Katherine Archuleta that the unauthorized access to OPM’s systems was achieved by compromising user credentials from a contractor, KeyPoint Government Solutions, that was itself the victim of a cyberattack resulting in a data breach of information on thousands of government employees. The implication is that after the intrusion into its contractor’s systems, OPM failed to disable or change credentials it had issued to KeyPoint personnel. Imagine a homeowner who has given a spare house key to his neighbor and, upon learning his neighbor’s house was robbed, chooses not to have his locks changed. The successful use of credentials issued to a contractor is reminiscent of other high-profile data breaches, including the theft of customer information from Home Depot and Target, where hackers first compromised a third party vendor to gain access to the primary target.

Subpoena? Court order? Search warrant? How the government can get your data

After a full 11-judge en banc panel of the U.S Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit reversed a ruling made last June by a 3-judge panel of the same Court, deciding that government law enforcement agents do not need a search warrant to obtain cell tower location data about individuals, the attorney for appellant Quartavious Davis came to a dire conclusion about what the ruling meant. As quoted in a May 5 Washington Post article about the ruling, lawyer David Oscar Markus called the opinion “breathtaking,” declaring, “It means that the government can get anything stored by a third party – your Facebook posts, your Amazon purchases, your Internet search history, even the documents and pictures you store in the cloud, all without a warrant.” It’s understandable that Markus would be upset, frustrated, and possibly even confused by the ruling, but his hyperbolic statement suggests either that he was speaking with emotion rather than reason or that he suffers from a lack of understanding about current search doctrine in the United States.

In the en banc opinion for United States v. Quartavious Davis, Circuit Judge Frank Hull wrote the majority opinion with explicit attention to detail regarding the nature of the information that the government sought about Davis’ cell phone use in its court order to wireless carrier MetroPCS. As a form of electronic communications, cell phone activity falls under the purview of the Electronic Communications Privacy Act (ECPA) and, more importantly, the Stored Communications Act (SCA) portion of that law. In the Davis case, the government obtained a court order (but not a search warrant) for MetroPCS records that included all the numbers Davis called over a 67-day period and identifying information for the cell tower that connected the calls. The government used the tower identifiers to determine the exact physical location of each of the towers and used that location information tied to each call as evidence that Davis was near the location of six armed robberies, for which he and several accomplices were indicted, around the time the robberies occurred. The Court’s opinion notes that the government neither requested nor received information about the contents of Davis’ calls, or any real-time location information for Davis’ phone. This distinction is important because the SCA requires the government to obtain a search warrant for the contents of electronic communications, but not for records about such communication.

The SCA lays out statutory requirements under which the government can require an electronics communication service provider (like a cellular carrier) to disclose customer records, including the contents of customer communications or records about those communications. The regulations for different types of information differ in what type of government request is required, ranging from a search warrant (the highest legal standard) to a simple subpoena. In general, the government has to meet a higher burden to get a judge to issue a search warrant than a court order (a subpoena can also be issued by a judge but may also be issued by a district attorney, lawyer, or other authorized official. In its investigation of Davis, the government relied on a section of the SCA that requires only a court order (not a search warrant) if it can show that the records sought are “relevant and material to an ongoing criminal investigation.” (18 U.S.C. §2703(d)). The statute is clearly written and, at least in Davis’ case, there was no question that the government satisfied the requirements necessary to obtain the court order.

Back to Markus’ warning about what this ruling means. The ECPA and SCA cover many kinds of electronic communications, including wireless and landline telephone use, text messaging, email, and other forms of data transfer over wired networks or radio frequencies, as well as “remote computer use” such as hosted email services, search engines, document storage, and social media. Records related to these types of activities can and are requested by law enforcement, but where the records include communications contents the government is still required to get a search warrant before a provider discloses data to them. Major service providers typically cite the SCA (specifically §2701 and §2703) in their public notices regarding compliance with requests from law enforcement. Some law enforcement guidelines, like those for Apple and Microsoft, are publicly available. A quick review of such guidelines highlights the distinction between types of data that can be obtained with a subpoena (subscriber information), court order (customer usage or purchase records), or a search warrant (email contents, documents in online cloud storage). Nothing in the 11th Circuit Court ruling changes the categorization of any consumer content to require a lower legal standard.

SecurityArchitecture.com

SecurityArchitecture.com