OPM (finally) notifies people affected by breach

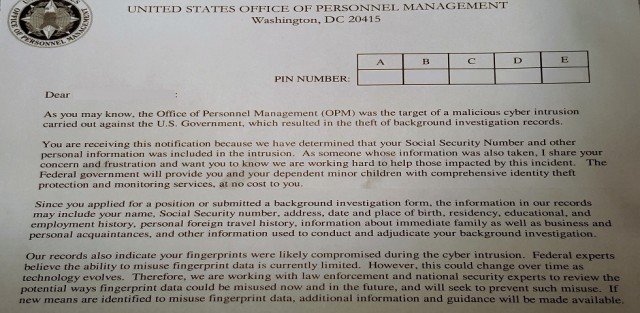

On June 9, 2015, the U.S. Office of Personnel Management (OPM) publicly announced the results of a computer forensic investigation – initiated many months earlier – indicating that background investigation records on as many as 22 million individuals had been compromised in a long-term intrusion into the agency’s computer systems. As noted in the OPM press release, it discovered the security incident resulting in the breach in April, and after further analysis determined that unauthorized access to OPM personnel and background investigation records had begun nearly a year earlier, in May 2014. It’s not entirely clear why OPM waited almost two months to publicly disclose the breach, but affected individuals have had to wait much longer to receive notification from OPM confirming their information was among the compromised records. OPM first had to hire a contractor to help it conduct the notification campaign and provide support to affected individuals, so it did not start sending notifications until the beginning of October. Given the large number of recipients, it should come as no surprise that the notification process has been drawn out; my letter from OPM arrived on November 23, 137 days after the public announcement and approximately 200 days after OPM says it discovered the incident.

The significant time lag associated with notification is troubling on several fronts, at least for those affected by the breach, but the simple fact is that there are no regulations or guidelines currently in force that compel OPM or any other federal agency to act faster on its notifications. All U.S. federal agencies are required, under rules issued by the Office of Management and Budget in May 2007 in Memorandum M-07-16, to notify the U.S. Computer Emergency Readiness Team (US-CERT) of “unauthorized access or any incident involving personally identifiable information” within one hour of discovery. The OMB rules do not specify an explicit notification timeline, but do say that notification should be provided “without unreasonable delay” following the discovery of a breach. After the recent series of large-scale breaches of personal information by private sector entities, the Obama Administration and both houses of Congress have proposed legislation that would, among other things, impose strict notification timelines for data breachs. As part of a broader set of initiatives intended to protect consumers, the Administration in January suggested a Personal Data Notification and Protection Act that, like the Senate’s version (S. 177) of the Data Security and Breach Notification Act, would require breach notification within 30 days. The House version (H.R. 1770), introduced three months later than the Senate’s bill, shortens the notification deadline to 25 days. None of these pieces of legislation have been enacted but even if they had they would presumably not bind OPM or other federal agencies, because they are intended to introduce statutory provisions enforced by the Federal Trade Commission that apply to entities that fall under FTC authority. It’s difficult to understand why government agencies should be continue to make their own definitions of what constitutes an “unreasonable delay” if commercial and non-profit organizations are to be expected to notify breach victims within 30 days.

The significant time lag associated with notification is troubling on several fronts, at least for those affected by the breach, but the simple fact is that there are no regulations or guidelines currently in force that compel OPM or any other federal agency to act faster on its notifications. All U.S. federal agencies are required, under rules issued by the Office of Management and Budget in May 2007 in Memorandum M-07-16, to notify the U.S. Computer Emergency Readiness Team (US-CERT) of “unauthorized access or any incident involving personally identifiable information” within one hour of discovery. The OMB rules do not specify an explicit notification timeline, but do say that notification should be provided “without unreasonable delay” following the discovery of a breach. After the recent series of large-scale breaches of personal information by private sector entities, the Obama Administration and both houses of Congress have proposed legislation that would, among other things, impose strict notification timelines for data breachs. As part of a broader set of initiatives intended to protect consumers, the Administration in January suggested a Personal Data Notification and Protection Act that, like the Senate’s version (S. 177) of the Data Security and Breach Notification Act, would require breach notification within 30 days. The House version (H.R. 1770), introduced three months later than the Senate’s bill, shortens the notification deadline to 25 days. None of these pieces of legislation have been enacted but even if they had they would presumably not bind OPM or other federal agencies, because they are intended to introduce statutory provisions enforced by the Federal Trade Commission that apply to entities that fall under FTC authority. It’s difficult to understand why government agencies should be continue to make their own definitions of what constitutes an “unreasonable delay” if commercial and non-profit organizations are to be expected to notify breach victims within 30 days.

Individuals affected by the OPM breach have been offered three years of credit monitoring and identity theft protection through ID Experts, an independent commercial firm specializing in these services to which OPM awarded a $133 million contract in September. Recipients of notification letters (there are two versions, depending on whether an individual’s fingerprints may have been included in the breach) can enroll in the MyIDCare service using a 25-character PIN and following a multi-step enrollment process (including an identify verification step using an Experian service, which T-Mobile subscribers in particular might find ironic). The privacy policy associated with MyIDCare identifies not ID Experts but CS Identity Corporation (CSID) as the provider of the identity theft protection service; CSID is essentially a wholesaler reseller of its services to companies like ID Experts. There is little in the privacy policy that is remarkable, although for users of CSID’s services who don’t come to the company via a U.S. entity like OPM, the reference in the policy to compliance with the U.S. – E.U. safe harbor framework seems due for revision. ID Experts’ privacy policy suffers from the same problem, but that is largely irrelevant where the OPM-sponsored services are concerned. Still, individuals affected by the OPM breach can be expected to have an interest in privacy practices of the service provider contracted to ostensibly protect them from future harm (at least for three years), so it is unfortunate that MyIDCare subscribers may potentially be confused by the existence of multiple privacy policies linking back to different corporate entities.

SecurityArchitecture.com

SecurityArchitecture.com