Subpoena? Court order? Search warrant? How the government can get your data

After a full 11-judge en banc panel of the U.S Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit reversed a ruling made last June by a 3-judge panel of the same Court, deciding that government law enforcement agents do not need a search warrant to obtain cell tower location data about individuals, the attorney for appellant Quartavious Davis came to a dire conclusion about what the ruling meant. As quoted in a May 5 Washington Post article about the ruling, lawyer David Oscar Markus called the opinion “breathtaking,” declaring, “It means that the government can get anything stored by a third party – your Facebook posts, your Amazon purchases, your Internet search history, even the documents and pictures you store in the cloud, all without a warrant.” It’s understandable that Markus would be upset, frustrated, and possibly even confused by the ruling, but his hyperbolic statement suggests either that he was speaking with emotion rather than reason or that he suffers from a lack of understanding about current search doctrine in the United States.

In the en banc opinion for United States v. Quartavious Davis, Circuit Judge Frank Hull wrote the majority opinion with explicit attention to detail regarding the nature of the information that the government sought about Davis’ cell phone use in its court order to wireless carrier MetroPCS. As a form of electronic communications, cell phone activity falls under the purview of the Electronic Communications Privacy Act (ECPA) and, more importantly, the Stored Communications Act (SCA) portion of that law. In the Davis case, the government obtained a court order (but not a search warrant) for MetroPCS records that included all the numbers Davis called over a 67-day period and identifying information for the cell tower that connected the calls. The government used the tower identifiers to determine the exact physical location of each of the towers and used that location information tied to each call as evidence that Davis was near the location of six armed robberies, for which he and several accomplices were indicted, around the time the robberies occurred. The Court’s opinion notes that the government neither requested nor received information about the contents of Davis’ calls, or any real-time location information for Davis’ phone. This distinction is important because the SCA requires the government to obtain a search warrant for the contents of electronic communications, but not for records about such communication.

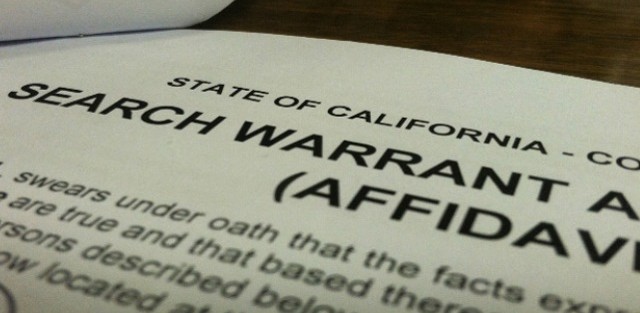

The SCA lays out statutory requirements under which the government can require an electronics communication service provider (like a cellular carrier) to disclose customer records, including the contents of customer communications or records about those communications. The regulations for different types of information differ in what type of government request is required, ranging from a search warrant (the highest legal standard) to a simple subpoena. In general, the government has to meet a higher burden to get a judge to issue a search warrant than a court order (a subpoena can also be issued by a judge but may also be issued by a district attorney, lawyer, or other authorized official. In its investigation of Davis, the government relied on a section of the SCA that requires only a court order (not a search warrant) if it can show that the records sought are “relevant and material to an ongoing criminal investigation.” (18 U.S.C. §2703(d)). The statute is clearly written and, at least in Davis’ case, there was no question that the government satisfied the requirements necessary to obtain the court order.

Back to Markus’ warning about what this ruling means. The ECPA and SCA cover many kinds of electronic communications, including wireless and landline telephone use, text messaging, email, and other forms of data transfer over wired networks or radio frequencies, as well as “remote computer use” such as hosted email services, search engines, document storage, and social media. Records related to these types of activities can and are requested by law enforcement, but where the records include communications contents the government is still required to get a search warrant before a provider discloses data to them. Major service providers typically cite the SCA (specifically §2701 and §2703) in their public notices regarding compliance with requests from law enforcement. Some law enforcement guidelines, like those for Apple and Microsoft, are publicly available. A quick review of such guidelines highlights the distinction between types of data that can be obtained with a subpoena (subscriber information), court order (customer usage or purchase records), or a search warrant (email contents, documents in online cloud storage). Nothing in the 11th Circuit Court ruling changes the categorization of any consumer content to require a lower legal standard.

SecurityArchitecture.com

SecurityArchitecture.com