Want to reduce unauthorized login attempts? Use Google Authenticator

If you have a public website, you should know that your site is regularly scanned and otherwise accessed, both by web “crawlers” from Google, Bing, and similar search engines and by individuals or agents with less benign intentions than cataloging your site’s pages. Websites running on popular platforms like WordPress or Joomla that expose their administrator and user login pages to public accessible with standards, predictable URL patterns are often targeted by intruders who attempt brute force login attacks to try to guess administrator passwords and gain access. There are many ways, on your own or through the use of available plugin applications, to keep these types of unauthorized attempts from being successful, but it is relatively difficult to prevent the attempts from occurring at all. The most effective methods for defending against brute force attacks and other types of unauthorized access attempts tend to focus on adding and configuring one or more .htaccess files to a website to control access to directories, files, and web server functionality. Many popular WordPress security plugins, for example, enable features that modify .htaccess files in combination with scripts that track the number of login attempts from an IP address or associated with a single username. This can provide login lockout functionality that both limits the number of failed attempts that can be made (thwarting brute force attacks) and prevents future access from IP addresses or agents that tried to log in.

With restrictions in place like limiting the number of login attempts and blacklisting IP addresses or address ranges, a website administrator can be relatively confident than an unauthorized user will not be able to gain access (assuming of course that good passwords are also employed for authorized user accounts). It can nevertheless be very difficult to significantly reduce unauthorized login attempts, particularly when attackers use automated botnets or distributed attack tools to vary their source IP addresses. It may seem like an improvement a site only allows one failed attempt per IP address, but if an attack uses hundreds or thousands of source computers, the volume of failed attempts can still cause performance problems for a targeted site (not to mention filling up the administrator’s email inbox with failed login notices). One good way to eliminate a greater proportion of these attempts than is possible through IP blacklisting is to implement some type of two-factor authentication.

With restrictions in place like limiting the number of login attempts and blacklisting IP addresses or address ranges, a website administrator can be relatively confident than an unauthorized user will not be able to gain access (assuming of course that good passwords are also employed for authorized user accounts). It can nevertheless be very difficult to significantly reduce unauthorized login attempts, particularly when attackers use automated botnets or distributed attack tools to vary their source IP addresses. It may seem like an improvement a site only allows one failed attempt per IP address, but if an attack uses hundreds or thousands of source computers, the volume of failed attempts can still cause performance problems for a targeted site (not to mention filling up the administrator’s email inbox with failed login notices). One good way to eliminate a greater proportion of these attempts than is possible through IP blacklisting is to implement some type of two-factor authentication.  There are several commercial and open-source alternatives available, including Duo Security, OTP Auth, and Google Authenticator, all of which have PHP-based implementations available that make them suitable for use with WordPress and many other web server and content management platforms. All of these tools work in essentially the same way, where the website or application and its users run a pseudo-random number generator initiated with the same seed value (so the series of numbers they produce match). Adding this type of two-factor authentication (2FA) to a login page means users will need to enter their username, password, and one-time code generated by software on a device under their control (typically a computer workstation or smartphone).

There are several commercial and open-source alternatives available, including Duo Security, OTP Auth, and Google Authenticator, all of which have PHP-based implementations available that make them suitable for use with WordPress and many other web server and content management platforms. All of these tools work in essentially the same way, where the website or application and its users run a pseudo-random number generator initiated with the same seed value (so the series of numbers they produce match). Adding this type of two-factor authentication (2FA) to a login page means users will need to enter their username, password, and one-time code generated by software on a device under their control (typically a computer workstation or smartphone).

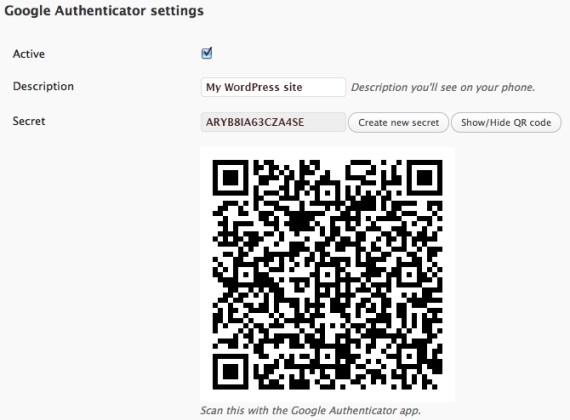

This post discusses Google Authenticator as a representative example (the tool has apps for both Android and iOS devices, is used on Google sites and many third-party services, and can be added to WordPress sites via a free plugin). Setting up 2FA on a Google-enabled site entails generating a shared secret stored by Google Authenticator and the end user’s device. The smartphone apps allow users to scan a QR code or manually enter the secret, as shown below (note: neither the secret nor the QR code in the image are actual Google Authenticator settings).

This post discusses Google Authenticator as a representative example (the tool has apps for both Android and iOS devices, is used on Google sites and many third-party services, and can be added to WordPress sites via a free plugin). Setting up 2FA on a Google-enabled site entails generating a shared secret stored by Google Authenticator and the end user’s device. The smartphone apps allow users to scan a QR code or manually enter the secret, as shown below (note: neither the secret nor the QR code in the image are actual Google Authenticator settings).

On WordPress sites, installing the Google Authenticator plugin modifies the login page to add a third field for the one-time code (which changes every 30 seconds). While no means a perfect solution, the way many automated probes and scripts seem to work, encountering a login page with an additional 2FA field prevents the submission of the login form or (depending on the specific tools) generates a form error separate from the failed login or HTTP 404 errors commonly associated with unauthorized access attempts.

On WordPress sites, installing the Google Authenticator plugin modifies the login page to add a third field for the one-time code (which changes every 30 seconds). While no means a perfect solution, the way many automated probes and scripts seem to work, encountering a login page with an additional 2FA field prevents the submission of the login form or (depending on the specific tools) generates a form error separate from the failed login or HTTP 404 errors commonly associated with unauthorized access attempts.

SecurityArchitecture.com

SecurityArchitecture.com